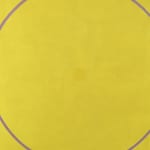

William Turnbull 1922-2012

Untitled (Yellow Violet Arc), 1962

oil on canvas

79 7/8 x 59 7/8 inches

203 x 152 cm

203 x 152 cm

dated on the stretcher bar

Further images

While notionally abstract, the circle motif in Untitled (Yellow Violet Arc), looks back to the paintings of human heads that William Turnbull was making in the mid-1950s. Over time, this...

While notionally abstract, the circle motif in Untitled (Yellow Violet Arc), looks back to the paintings of human heads that William Turnbull was making in the mid-1950s. Over time, this head image evolves and reconfigures, beginning as a loose gathering of marks, then flatly drawn circles. Later, these circles increase in scale, becoming various sections of a curve. Here we are presented with an incomplete motif – the circle is cut off at the sides – suggesting it has expanded outwards from the centre point. The character of the circle is quite different to the images that precede it – the line is thin and sharp and its shape particularly perfect and symmetrical when compared with the softer, filled-in circle of 15-1959. The precision of this line and its symmetry effect an inward focus to the image, which is intensified by the small circle of yellow within the larger violet arcs. This centre point within the circle suggests the image of a navel – a figurative association that might be overlooked were it not for its earlier appearance, inscribed on the torso of Idol 4, 1956, and its later recurrence on the bronze Female Figure, 1989.

The navel appears in many cultures as a symbol of life cycle and rebirth – it is particularly significant within the Hindu faith as the sacral chakra (the word chakra itself means ‘wheel’ or ‘circle of energy’) and the source of the god Brahma, who is said to have emerged from a lotus flower that grew from the navel of Vishnu.

The image of the circle (ensō in Japanese) is one of the most important symbols in Zen Buddhism, presenting a number of dualities – fullness and emptiness, perfection and imperfection, movement and stillness. The practice of making ensō ink drawings has been used for centuries as part of a daily meditative routine. An incomplete circle may express various ideas – for example, that the ensō is not separate but is part of something greater, or that imperfection is an essential and inherent aspect of existence.

In a 1973 review in the journal Kunstforum, Frank Whitford highlighted Turnbull’s affinity with East Asian art and the meditative nature of his paintings:

‘Turnbull wants to create objects – like the navel for the holy Hindu – which serve as an outward focus for an inward spiritual contemplation. The viewer should give much of himself to the artwork in order to sink deeper into his own personality and to understand himself better. The simpler the form, the richer the discovery of self. Turnbull’s works indicate the strict and dry understatement of Scottish Christianity, and possess the inner silence of a Japanese temple garden.’ 1

1 Frank Whitford, ‘Zen of the Presbyterians’, Kunstforum, October 1973, pp205 – 210

The navel appears in many cultures as a symbol of life cycle and rebirth – it is particularly significant within the Hindu faith as the sacral chakra (the word chakra itself means ‘wheel’ or ‘circle of energy’) and the source of the god Brahma, who is said to have emerged from a lotus flower that grew from the navel of Vishnu.

The image of the circle (ensō in Japanese) is one of the most important symbols in Zen Buddhism, presenting a number of dualities – fullness and emptiness, perfection and imperfection, movement and stillness. The practice of making ensō ink drawings has been used for centuries as part of a daily meditative routine. An incomplete circle may express various ideas – for example, that the ensō is not separate but is part of something greater, or that imperfection is an essential and inherent aspect of existence.

In a 1973 review in the journal Kunstforum, Frank Whitford highlighted Turnbull’s affinity with East Asian art and the meditative nature of his paintings:

‘Turnbull wants to create objects – like the navel for the holy Hindu – which serve as an outward focus for an inward spiritual contemplation. The viewer should give much of himself to the artwork in order to sink deeper into his own personality and to understand himself better. The simpler the form, the richer the discovery of self. Turnbull’s works indicate the strict and dry understatement of Scottish Christianity, and possess the inner silence of a Japanese temple garden.’ 1

1 Frank Whitford, ‘Zen of the Presbyterians’, Kunstforum, October 1973, pp205 – 210

Provenance

Estate of the Artist