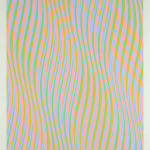

Bridget Riley b. 1931

Untitled (related to "Song of Orpheus"), 1979

pencil and gouache on paper

38 1/2 x 24 3/8 inches

97.8 x 62 cm

97.8 x 62 cm

Signed, dated, and inscribed lower recto (RILBR0383)

This work on paper follows after Bridget Riley’s 1978 Song of Orpheus series, a group of five acrylic on canvas paintings, numbered 1-5. It also relates to Orphean Elegy 1,...

This work on paper follows after Bridget Riley’s 1978 Song of Orpheus series, a group of five acrylic on canvas paintings, numbered 1-5. It also relates to Orphean Elegy 1, 2, 4, 7 and an untitled mural format picture (BR 192), painted in 1978 and Orphean Elegy 5 and 6, painted in 1979 , which have a similar composition but use a slightly ‘deeper’ palette. For the Song of Orpheus series, Riley expanded the number of colours she was using in her paintings from three to five, and these same five, tonally similar colours - pink, lilac, green, blue and yellow - are used in the present work.

Between the mid-1970s and 1980, Riley reintroduced the curve into her paintings, to further extend her exploration of colour interaction and its relationship with light. The resulting body of work reveals new levels of complexity in terms of formal experimentation as well as poetic presence. By treating the curve as a rhythmic vehicle, which broke down the assertive structure of the stripe paintings, Riley was able to reach new heights of colour interaction. The curve meant that new colour relationships could become 'released' and react together within the more dynamic composition – a compositional motif first explored in the early painting, Cataract 3, 1967.

Riley discovered that the length of the edge is crucial in facilitating this flux and as such these pictures are made up of ‘twisted’ curves. She explained in 1978, ‘When colours are twisted along the rise and fall of a curve their juxtapositions change continuously. There are innumerable sequences each of which throws up a different sensation. From these I build up clusters which then flow one into another almost imperceptibly.’

She added later that ‘I found that the tapering, or as you say 'attenuated', ends of such twisted bands were most sensitive to colour inflections of all sorts and began to use them in curve structures which intensified the effect of the disembodied colours. The rise and fall of these curves had to be precisely calculated for each group of paintings, and so I had to make templates as I needed them... I organised this fluctuating activity by bunching it up in clusters which emphasise one shift or another'.

In the present study the lines of the curve dissolve and expand continuously, recalling the vibrancy and movement of light reflecting off rippling water. This sensation, that the work is in constant flux, is a direct result of the complex colour arrangement, Riley’s colours having been carefully selected according their positions on the colour circle. It is the interrelationship of theses five colours which determines the effects that can be generated. As the artist explained,

‘Each relate to one another in such a way that, if one assembles them as they would be in the colour circle, they describe the shape of a pentagon. Each colour is in such a position that its complementary would be exactly between the two colours opposite… For example magenta, the complementary to the painted green, would lie between the actual violet and pink if it were painted. However, as it is not painted it is instead evoked by the colours present. At the same time, neighbouring complementaries are fusing visually: if the yellow is next to the pink the fugitive orange appears; and again, if that same yellow is bordered by the green or even by the blue, different yellow-greens appear. So I am dealing with both at once - the fusion of harmonies and the evocation of complementaries.’

The simultaneous contrast of these colours moving together, side by side, and the play of light created by this movement is truly mesmerising. But the appeal of Riley’s images lies beyond optical sensation alone. While her images can be immersive, their dizzying imagery acting directly on the body, they also activate our sense memory, speaking to previous aesthetic experiences on an unconscious level. It is this elusive quality of feeling which gives her paintings their emotional resonance and is analogous to an experience of listening to music, reading poetry or being surrounded by nature.

As she explained, ‘My paintings are, of course, concerned with generating visual sensations, but certainly not to the exclusion of emotion. One of my aims is that these two responses shall be experienced as one and the same.’

Between the mid-1970s and 1980, Riley reintroduced the curve into her paintings, to further extend her exploration of colour interaction and its relationship with light. The resulting body of work reveals new levels of complexity in terms of formal experimentation as well as poetic presence. By treating the curve as a rhythmic vehicle, which broke down the assertive structure of the stripe paintings, Riley was able to reach new heights of colour interaction. The curve meant that new colour relationships could become 'released' and react together within the more dynamic composition – a compositional motif first explored in the early painting, Cataract 3, 1967.

Riley discovered that the length of the edge is crucial in facilitating this flux and as such these pictures are made up of ‘twisted’ curves. She explained in 1978, ‘When colours are twisted along the rise and fall of a curve their juxtapositions change continuously. There are innumerable sequences each of which throws up a different sensation. From these I build up clusters which then flow one into another almost imperceptibly.’

She added later that ‘I found that the tapering, or as you say 'attenuated', ends of such twisted bands were most sensitive to colour inflections of all sorts and began to use them in curve structures which intensified the effect of the disembodied colours. The rise and fall of these curves had to be precisely calculated for each group of paintings, and so I had to make templates as I needed them... I organised this fluctuating activity by bunching it up in clusters which emphasise one shift or another'.

In the present study the lines of the curve dissolve and expand continuously, recalling the vibrancy and movement of light reflecting off rippling water. This sensation, that the work is in constant flux, is a direct result of the complex colour arrangement, Riley’s colours having been carefully selected according their positions on the colour circle. It is the interrelationship of theses five colours which determines the effects that can be generated. As the artist explained,

‘Each relate to one another in such a way that, if one assembles them as they would be in the colour circle, they describe the shape of a pentagon. Each colour is in such a position that its complementary would be exactly between the two colours opposite… For example magenta, the complementary to the painted green, would lie between the actual violet and pink if it were painted. However, as it is not painted it is instead evoked by the colours present. At the same time, neighbouring complementaries are fusing visually: if the yellow is next to the pink the fugitive orange appears; and again, if that same yellow is bordered by the green or even by the blue, different yellow-greens appear. So I am dealing with both at once - the fusion of harmonies and the evocation of complementaries.’

The simultaneous contrast of these colours moving together, side by side, and the play of light created by this movement is truly mesmerising. But the appeal of Riley’s images lies beyond optical sensation alone. While her images can be immersive, their dizzying imagery acting directly on the body, they also activate our sense memory, speaking to previous aesthetic experiences on an unconscious level. It is this elusive quality of feeling which gives her paintings their emotional resonance and is analogous to an experience of listening to music, reading poetry or being surrounded by nature.

As she explained, ‘My paintings are, of course, concerned with generating visual sensations, but certainly not to the exclusion of emotion. One of my aims is that these two responses shall be experienced as one and the same.’

Provenance

Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, London

David Zwirner, Hong Kong