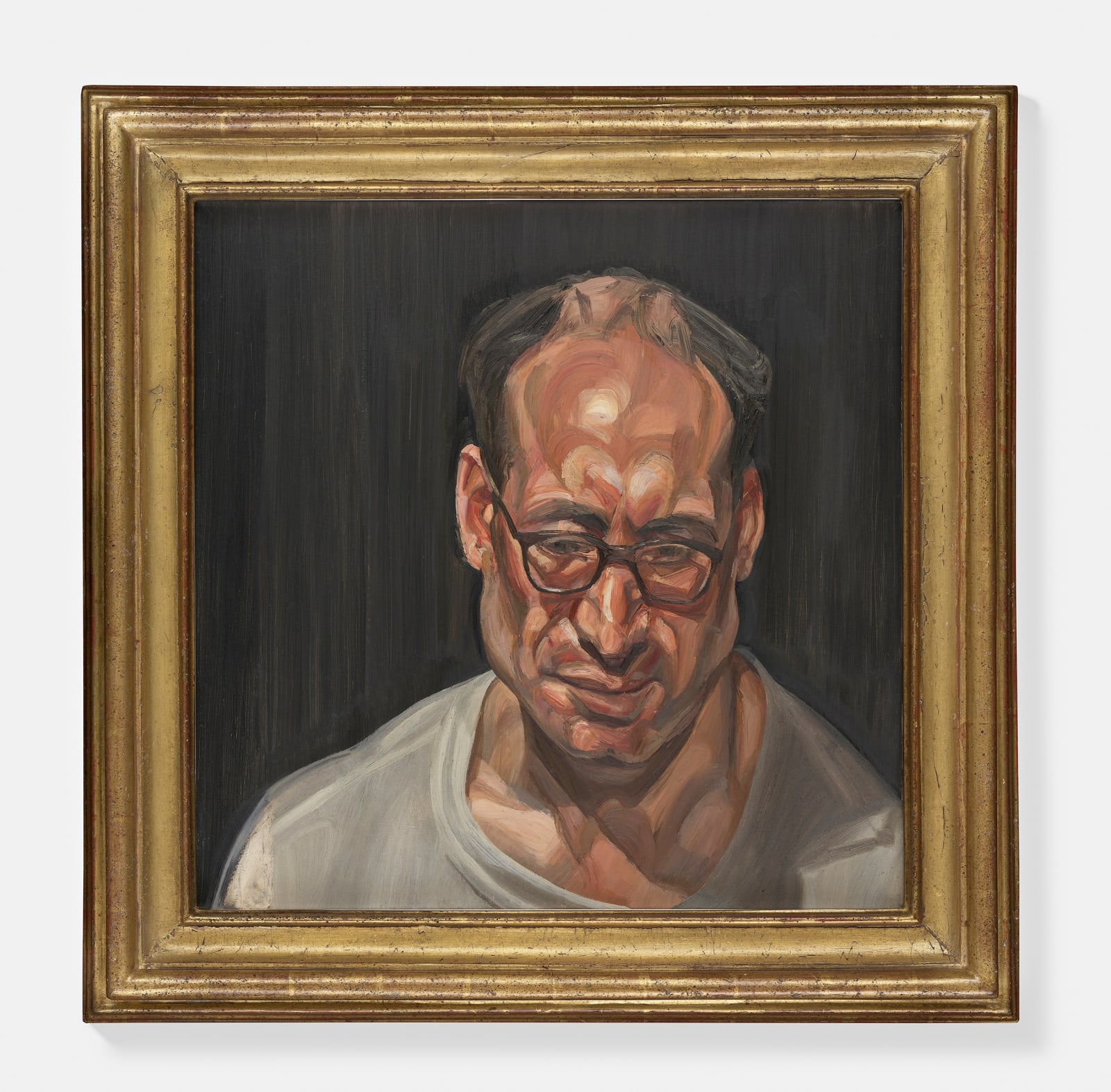

Lucian Freud 1922-2011

Man with Glasses, c.1963-64

oil on canvas

24 1/8 x 24 1/8 inches

61 x 61 cm

61 x 61 cm

When Lucian Freud first met Harry Diamond (1924 – 2009) in 1944, he was ‘eking out a living on the margins of Soho,’ working as a stagehand at various London...

When Lucian Freud first met Harry Diamond (1924 – 2009) in 1944, he was ‘eking out a living on the margins of Soho,’ working as a stagehand at various London theatres and juggling a number of other odd jobs – at one point, he was a bookseller, at another, a cleaner for Ronnie Scott’s jazz club, later achieving relative success as a photographer.1 Ever present on the bohemian Soho scene, Diamond was well acquainted with other School of London painters such as Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon and Michael Andrews, and, after taking up photography full-time in the late 1960s, was known to exchange photographs he had taken of these artists and their work for a drink or a meal.2

Man with Glasses is the third in a series of four portraits that Freud made of Diamond over an almost 20-year period (1951 – 1970). While of the four paintings Interior at Paddington, 1951, which won Freud the Arts Council prize at the Festival of Britain, is undoubtedly the most renowned, Diamond identified the present work and the highly similar earlier composition Man in a Mackintosh, 1957 – 58 as his preferred portraits – perhaps he felt they best reflected his character.3

Modelling for Freud was an intense and sustained process, each sitting would last for several hours and occurred over many months, sometimes years, and even if Freud was painting the background of a portrait, he would require his sitter, as he believed a successful work would only result from the ‘living presence’ of his subject, as he explained:

‘The subject must be kept under closest observation: if this is done, day and night, the subject – he, she, or it – will eventually reveal the all, without which selection itself is not possible; they will reveal it, through some and every facet of their lives, or lack of life, through movements and attitudes, through every variation from one to another.’ 4 Michael Wishart, who posed for Boy with a Pigeon, 1944, likened his experience of sitting for Freud to undergoing ‘delicate eye surgery’, while Diamond himself recalled,

‘The sittings went on for some six months (…) another time it took a year – which was very demanding. We talked quite a lot, except at those times when he said, “Now don't talk, I'm concentrating”, which was fair enough. It was quite an ordeal. If someone is interested in getting your essence down on canvas, they are also drawing your essence out of you. Afterwards one felt depleted, but also invigorated.’ 5

By the time Freud came to make this third portrait of Diamond, the pair had been friends for two decades and accrued countless hours of studio time together. In this powerful, yet tender image there is a real sense of rawness and honesty, a result of the bond they had undoubtedly formed at this point and the artist’s sustained enquiry into both the physical appearance and emotional character of his sitter. While in Freud’s first and last portraits of Diamond his entire figure is portrayed within a setting, here the artist removes all extraneous detail from the composition, focusing solely on his sitter’s head and shoulders, which span the width of the canvas. Arguably the most visually compelling of the four portraits of Diamond, here he is seen emerging from the darkness, the cool, grey-black tones of the background heightening the luminosity of his skin, which is made up of an innumerable array of fleshy tones. Diamond’s head is tilted downwards and his eyes are averted, allowing us to scrutinise and explore the mutable, plastic qualities that make up his physiognomy and to contemplate his brooding expression, which wonderfully reflects Bruce Bernard’s description of him as a ‘complex and sensitive man’.6

Tired of being referred to as ‘The Ingres of Existentialism’ (as dubbed by Herbert Read) and buoyed by his close friend, Francis Bacon’s approach to painting, in the 1960s Freud embarked on a new, more expressive visual language for his art; ‘When people went on about my technique and how it related to the German old masters I have to say it was sickening. Especially when they went on about technique. I think that Francis’ way of painting freely helped me feel more daring.’ 7 Freud moved away from the meticulous, sable brush technique he’d perfected in the previous decade, adopting a looser, more emphatic application of paint. Here he has used hog hair brushes to apply oil in thick, broad strokes, effectively carving out the contours of Diamond’s strong jawline, prominent nose, large lips, dimpled chin and almond-shaped eyes.

Diamond’s photographs feature in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery, the Arts Council and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Following Diamond’s death, his photographic archive was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery.

1 Martin Gayford, Mark Holborn (Ed.), Lucian Freud, Volume 1, Phaidon Press, London, 2018, p19

2 Diamond featured in a black and white photograph on the cover of Frank Norman's 1959 book about Soho, entitled Stand on Me

3 Interior at Paddington was also the artist’s first large-scale painting and public commission

4 Lucian Freud, ‘Some Thoughts on Painting’, Encounter, London, July 1954

5 Harry Diamond, 1970, cited in Martin Gayford, ‘Arts: I was framed by Freud’, Independent, 24 February 1999:

www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/arts-i-was-framed-by-freud-1072877.html

6 Harry Diamond obituary, The Guardian, 27 January 2010:

www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/jan/27/harry-diamond-obituary

7 The artist quoted in ‘A Late-Night conversation with Lucian Freud’, Sebastian Smee, Freud at Work, London 2006, p18

Man with Glasses is the third in a series of four portraits that Freud made of Diamond over an almost 20-year period (1951 – 1970). While of the four paintings Interior at Paddington, 1951, which won Freud the Arts Council prize at the Festival of Britain, is undoubtedly the most renowned, Diamond identified the present work and the highly similar earlier composition Man in a Mackintosh, 1957 – 58 as his preferred portraits – perhaps he felt they best reflected his character.3

Modelling for Freud was an intense and sustained process, each sitting would last for several hours and occurred over many months, sometimes years, and even if Freud was painting the background of a portrait, he would require his sitter, as he believed a successful work would only result from the ‘living presence’ of his subject, as he explained:

‘The subject must be kept under closest observation: if this is done, day and night, the subject – he, she, or it – will eventually reveal the all, without which selection itself is not possible; they will reveal it, through some and every facet of their lives, or lack of life, through movements and attitudes, through every variation from one to another.’ 4 Michael Wishart, who posed for Boy with a Pigeon, 1944, likened his experience of sitting for Freud to undergoing ‘delicate eye surgery’, while Diamond himself recalled,

‘The sittings went on for some six months (…) another time it took a year – which was very demanding. We talked quite a lot, except at those times when he said, “Now don't talk, I'm concentrating”, which was fair enough. It was quite an ordeal. If someone is interested in getting your essence down on canvas, they are also drawing your essence out of you. Afterwards one felt depleted, but also invigorated.’ 5

By the time Freud came to make this third portrait of Diamond, the pair had been friends for two decades and accrued countless hours of studio time together. In this powerful, yet tender image there is a real sense of rawness and honesty, a result of the bond they had undoubtedly formed at this point and the artist’s sustained enquiry into both the physical appearance and emotional character of his sitter. While in Freud’s first and last portraits of Diamond his entire figure is portrayed within a setting, here the artist removes all extraneous detail from the composition, focusing solely on his sitter’s head and shoulders, which span the width of the canvas. Arguably the most visually compelling of the four portraits of Diamond, here he is seen emerging from the darkness, the cool, grey-black tones of the background heightening the luminosity of his skin, which is made up of an innumerable array of fleshy tones. Diamond’s head is tilted downwards and his eyes are averted, allowing us to scrutinise and explore the mutable, plastic qualities that make up his physiognomy and to contemplate his brooding expression, which wonderfully reflects Bruce Bernard’s description of him as a ‘complex and sensitive man’.6

Tired of being referred to as ‘The Ingres of Existentialism’ (as dubbed by Herbert Read) and buoyed by his close friend, Francis Bacon’s approach to painting, in the 1960s Freud embarked on a new, more expressive visual language for his art; ‘When people went on about my technique and how it related to the German old masters I have to say it was sickening. Especially when they went on about technique. I think that Francis’ way of painting freely helped me feel more daring.’ 7 Freud moved away from the meticulous, sable brush technique he’d perfected in the previous decade, adopting a looser, more emphatic application of paint. Here he has used hog hair brushes to apply oil in thick, broad strokes, effectively carving out the contours of Diamond’s strong jawline, prominent nose, large lips, dimpled chin and almond-shaped eyes.

Diamond’s photographs feature in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery, the Arts Council and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Following Diamond’s death, his photographic archive was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery.

1 Martin Gayford, Mark Holborn (Ed.), Lucian Freud, Volume 1, Phaidon Press, London, 2018, p19

2 Diamond featured in a black and white photograph on the cover of Frank Norman's 1959 book about Soho, entitled Stand on Me

3 Interior at Paddington was also the artist’s first large-scale painting and public commission

4 Lucian Freud, ‘Some Thoughts on Painting’, Encounter, London, July 1954

5 Harry Diamond, 1970, cited in Martin Gayford, ‘Arts: I was framed by Freud’, Independent, 24 February 1999:

www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/arts-i-was-framed-by-freud-1072877.html

6 Harry Diamond obituary, The Guardian, 27 January 2010:

www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/jan/27/harry-diamond-obituary

7 The artist quoted in ‘A Late-Night conversation with Lucian Freud’, Sebastian Smee, Freud at Work, London 2006, p18

Provenance

The ArtistPrivate Collection, gifted from the above

Lefevre Gallery, London

Private Collection, Europe

Exhibitions

London, Thomas Gibson Fine Art, British Art: A Post War Selection, 24 April - 22 May 2006, illus colour p2 & 15Literature

William Feaver, Lucian Freud, Rizzoli, New York,2007, illus colour p1228

of

8